Spending on drugs dropped by 32% since 2010. And the country owes international drug makers 1.1 billion euros ($1.2 billion), according to the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations.

Evangelisimos is the biggest hospital in Greece. With 1,000 beds, it is constantly running 10% to 20% over capacity. “There is just too many patients and not enough rooms,” trainee nurse Anastasia Karkasina said. Karkasina is three months away from becoming fully qualified. She is worried about getting a job.

“There are no available positions, because there is no money to pay for them,” she said while taking a short break with fellow trainee Anna Karafoti in the sizzling heat outside the hospital. If the two manage to get jobs, they can expect monthly salaries of about 700 euros ($780).”

A public health tragedy is surely looming, with under-staffed hospitals running at over-capacity.

It is worth looking twice at the last sentence in the CNN report above – there is no money in the system to pay the qualified nursing staff that the hospitals desperately need, and those fortunate enough to have work are paid just €700. This is a timely reminder of one of the most important ‘secondary’ effects of this crisis – the brain drain. Having to make crushing and unsustainable levels of debt repayments is one thing, but losing the skilled and trained members of the workforce who are best placed to help Greece do this is another. Alongside the immediate humanitarian crisis, this outflow of skilled labour will undermine the chances of recovery for at least a generation. According to Helena Smith, over 200,000 – or 2% of the population have emigrated since the crisis began.

“Of the 2% of the population who have left, more than half have gone to Germany and the UK. Migration outflows have risen 300% on pre-crisis levels, as youth unemployment soars to more than 50%. Around 55% of those affected by record rates of unemployment are under 35, according to Endeavour, the international nonprofit group that supports entrepreneurship.”

Even more concerning is the European University Institute Survey showing that 90% of those who have emigrated are university graduates, with 60% holding a Master’s degree and 11% a PhD. The human engine room of the Greek economy has been ripped out. Few countries could cope with this loss of human capital and it is hard to see at this stage what is left to kickstart the nosediving economy.

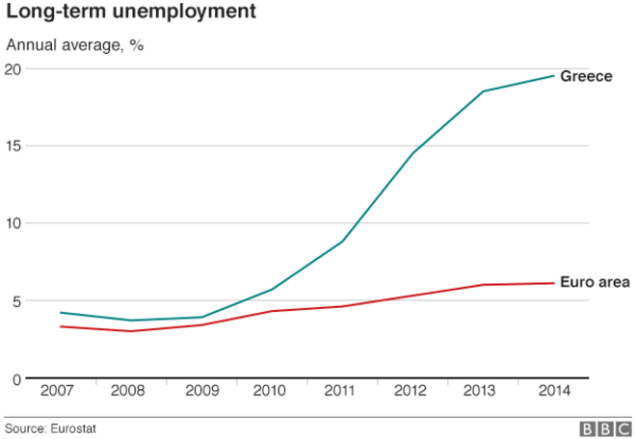

So those who can, often leave, and who can blame them. With unemployment at around 26%, and youth unemployment running at well over 50%, there is little room for optimism. According to the OECD, 30% of the Greek population now lives below the poverty line, with many unable to adequately feed themselves and their families. The number of those classed as homeless tripled between 2009 and 2013.

But within this nationwide tragedy it should be noted that not all have suffered the consequence of spending cuts and job losses. A study by Germany’s Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) has shown that top earners escaped the sharp end of the stick. Between 2008 and 2012, amid a raft of ‘fiscal adjustments’, taxation was increased by 337.7% for lower income households but by only 9% for those in the highest income bracket. Not only did “pauperisation” hit large parts of society – a fact that should be obvious to anyone with access to a TV or newspaper – but, of course, that inequality has risen sharply. As the New York Times has recently pointed out, while the more vulnerable in society are driven to financial ruin, “in central Athens and more affluent suburbs, the cafes are full of Greeks and tourists eating, drinking and talking until well past midnight.” Although finding accurate statistical data for Greece is always a challenge, the growth in inequality is reflected in the rise of the Gini coefficient – the most commonly used measure of inequality, ranging from 0 (complete equality) to 1 (complete inequality). Since 2009 it has increased from 0.331 to 0.345, cementing Greece’s place as one of Europe’s most unequal societies.

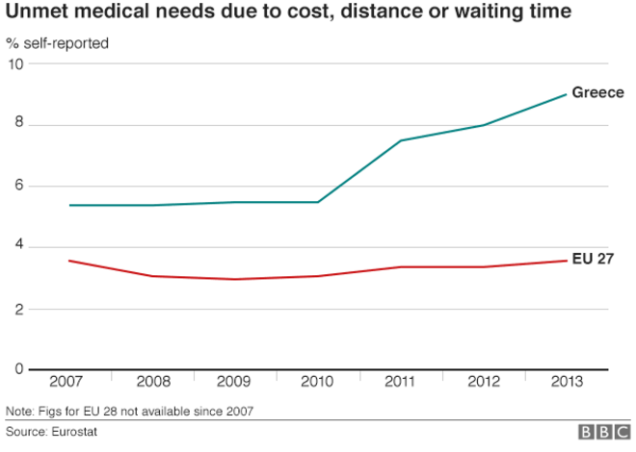

So beneath the political agendas and posturing we have a true humanitarian crisis, encompassing public health, homelessness, unemployment, and a widening gap between those at the top and those at the bottom. And as we know from the work of Wilkinson and Pickett among others, with growing inequality comes lower health, crime and society outcomes. Poverty can quickly become self-reinforcing, and the accompanying rise in inequality deeply destabilising. Factor in the loss of many of the most skilled and educated members of the workforce and we soon see that this is crisis from which Greece will not easily emerge. But at least the Euro dream survives to fight another day…