“Orderly debt restructuring has been done hundreds of times, hundreds, like with Germany in 1953”.

Pablo Iglesias

As the leader of Podemos has rightly pointed out on many occasions, sovereign debt restructuring is nothing new. Why, we may ask, should post-war Germany be helped to meet its financial commitments and rebuild its shattered economies, but Greece and other southern European states should not? Well, the standard narrative on the right is that after an initial helping hand, German productivity and fiscal acumen allowed it to become a regional manufacturing powerhouse. After West Germany had sufficiently re-established itself as a responsible and affluent member of the international community, it was then helped to reunite with its crumbling, post-communist sibling. The beauty of this simplistic version of events is that it is essentially a story of redemption and triumph over adversity, and so lends moral weight to Germany’s central role in contemporary European affairs. It does not, however, hold up to scrutiny of the facts. It was Germany’s central position in the cold war, as well as its divisive position in post-war Europe that made the USA aggressively promote it as a new capitalist powerhouse on the continent. By promoting the European Coal and Steel Community (the precursor to the modern EU) with German participation, the USA embarked on a project to strengthen the Deutschmark as an additional pillar of capitalist strength, and work towards the creation of a vast trading block. Nowhere is the commitment to rebuilding the German economy clearer than in the details of the 1953 debt restructuring, where debt repayment was tied to export revenue. Creditor nations therefore had a vested interest in buying German exports, thus allowing the indebted nation to repay its debts and become ultra-competitive on the global scene.

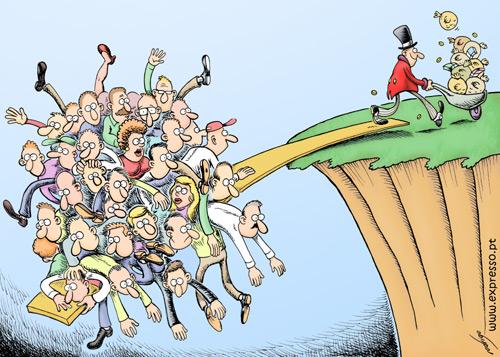

But in the 62 years that have passed since, the rules of the game have changed beyond recognition. The European project has boomed into a vast bureaucracy overseeing a continental marketplace. With the advent of the single currency at the beginning of the century, the Eurozone members committed themselves to the observance of strict financial rules in exchange for the so-called stability of a single unit of currency designed to reduce transaction costs and promote financial security within the bloc. It is now widely known that countries, including Greece, failed miserably to meet the requirements of euro entry but were admitted anyway through a combination of financial fraud and European bonhomie. Although this may look like a tragic mistake in hindsight, it was crucial to the project that the southern European countries join the single currency in an irreversible manner. As soon as Greece, Italy and Spain were locked into a currency position which did not allow for default, they had sacrificed their only effective means of making their economies more competitive in the face of German exports (which, as I previously discussed here, are made so competitive by breaking Eurozone rules). In short, they were therefore doomed to run current account deficits vis-à-vis Germany ad infinitum. But to make matters even worse, the lack of mechanism for fiscal transfer within the Eurozone (with the original rules explicitly removing this possibility) meant that there has never been any way for the German surplus to be recycled within the union in the interest of stability and balanced growth. The single currency has been deeply flawed from the start.

Continue reading →